[ad_1]

Aug. 20 was a great day within the pediatric intensive care unit at Kids’s Hospital New Orleans. Carvase Perrilloux, a two-month-old child who’d are available a couple of week earlier with respiratory syncytial virus and COVID-19, was lastly able to breathe with out the ventilator retaining his tiny physique alive. “You probably did it!” nurses in PPE cooed as they eliminated the tube from his airway and he took his first solo gasp, naked toes kicking.

Downstairs, Quintetta Edwards was getting ready for her 17-year-old son, Nelson Alexis III, to be discharged after spending greater than two weeks within the hospital with COVID-19—first within the ICU, then stabilizing on an acute-care flooring. “Happily, he by no means regressed,” Edwards says from exterior Nelson’s room, the door marked with indicators warning of potential COVID-19 publicity inside. “He’s progressing, slowly however absolutely.”

The nurses and medical doctors who look after the sickest sufferers at Kids’s Hospital New Orleans (CHNO) must take the great the place they’ll nowadays. On Aug. 6, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards introduced that greater than 3,000 youngsters statewide had been recognized with COVID-19 over the course of simply 4 days. That very same week, a couple of quarter of Louisiana youngsters examined for COVID-19 by the state’s largest well being system turned out to have the virus.

Medical employees line a corridor at Kids’s Hospital New Orleans. The hospital has employed about 150 new nurses to assist handle excessive affected person counts.

Kathleen Flynn for TIME

Seventy younger sufferers ended up in remedy at CHNO in the course of the 30 days ending Aug. 23. Previous to this summer season, the hospital had by no means needed to look after greater than seven COVID-19 sufferers at a time, and often fewer than that; on any given day in August, that quantity has been not less than within the mid-teens, sufficient that the power needed to name in a medical strike workforce from Rhode Island to assist handle the surge.

CHNO isn’t alone. The additional-transmissible Delta variant has ushered in a brand new chapter of the pandemic. For the primary time, pediatric hospitals are struggling to deal with the variety of younger sufferers creating extreme circumstances of COVID-19. A document excessive of greater than 1,900 youngsters have been hospitalized nationwide on Aug. 14—and in contrast to throughout earlier spikes, infections have to this point been clustered largely in states with low vaccine protection, which means hospitals in undervaccinated states like Louisiana, Florida, Tennessee, Alabama and Texas are drowning. “Our hospital system throughout Alabama is past capability. Final week we had web damaging ICU beds, and that’s pediatric and grownup collectively,” says Dr. David Kimberlin, co-director of the division of pediatric infectious ailments at Kids’s of Alabama. “Medical doctors are doing CPR at the back of pickup vehicles.”

This grim situation could seem surprising, given one of many pandemic’s long-standing silver linings: that youngsters, for essentially the most half, are spared from the worst of COVID-19. About 400 youngsters nationwide have died from COVID-19 for the reason that pandemic started, and most pediatric hospitals have seen not more than a handful of sufferers at a time—which makes the present surge within the South and components of the Midwest particularly unnerving.

There isn’t a proof that the Delta variant is inflicting extra extreme illness than earlier strains, says Dr. Sean O’Leary, vice chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) committee on infectious ailments. Lower than 2% of youngsters who’ve caught COVID-19 throughout this wave landed within the hospital—roughly the identical share as throughout earlier phases of the pandemic, based on a TIME evaluation of AAP and U.S. Division of Well being and Human Providers knowledge. An excellent smaller share of youngsters die from the illness, although some have gone on to develop issues just like the inflammatory situation MIS-C.

Two-month-old Carvase Perrilloux undergoes an extubation process, taking him off of the ventilator that has been retaining him alive.

Kathleen Flynn for TIME

The distinction appears to be that the extremely contagious Delta pressure is tearing via all demographic teams at a livid clip, at present contributing to the greater than 140,000 infections reported within the U.S. on any given day. It’s a miserable numbers sport: If 100 youngsters turn out to be contaminated, one or two would possibly find yourself within the hospital. Push the caseload as much as 180,000—the variety of youngsters recognized with the virus nationwide in the course of the week ending Aug. 19—and not less than 1,800 are prone to get sick sufficient to wish hospitalization.

Kids have additionally drawn a brief straw. Viruses are wily, looking for out and infecting susceptible hosts in any respect prices. With out licensed vaccines for folks youthful than 12, any youngster who has not beforehand been contaminated has no immunity in opposition to SARS-CoV-2, which means the virus successfully has free rein amongst America’s 50 million youngest residents. Even amongst older youngsters who can get vaccinated, charges are low: simply 35% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 45% of 16- and 17-year-olds are absolutely vaccinated, based on U.S. Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention knowledge.

Whereas every particular person youngster has a low likelihood of creating extreme illness, the present pediatric surge, which has been compounded by an low season spike in RSV and parainfluenza circumstances, has grave implications for well being care networks. Even earlier than the pandemic, well being care entry was a wrestle in components of the South and Midwest. In Arkansas, for instance, there is just one pediatric hospital system to serve the state’s greater than Three million residents. A rural hospital might have fewer than 10 ICU beds, which means even a small coronavirus surge might push it past its limits. “Down right here within the deep South, we’re getting slammed to the purpose the place, truthfully, our well being techniques could collapse,” Kimberlin says. “What which means is, in case you have a stroke, you die at house.”

There’s a cause pediatric ICUs are dangerously full in Tennessee and Texas however, not less than in the mean time, not Maryland and Massachusetts. In every of the latter two states, greater than 60% of residents are absolutely vaccinated; within the former, about 41% and 46%, respectively. States with excessive vaccination charges additionally are typically extra aggressive about different precautions, like indoor masks mandates.

There are exceptions—pediatric hospitalizations are ticking up in California (151 admissions this week vs. 68 a month in the past) and New York (46 vs. 20 a month in the past), two states with excessive vaccine protection—and nobody can predict what the virus will do sooner or later. Nevertheless it stands to cause that extra youngsters are getting sick in states like Louisiana, the place solely about 40% of the inhabitants is absolutely vaccinated and greater than 4,600 new diagnoses are being reported amongst its 4.6 million residents every day. “Children don’t are likely to drive what’s happening; they have an inclination to replicate what’s happening within the surrounding group,” O’Leary says.

That youngsters are largely on the mercy of the adults of their communities is without doubt one of the cruelest quirks of this surge. “It’s exhausting, since you don’t wish to be judgmental” of people that haven’t gotten the shot, says Dr. Michael Blancaneaux, an emergency drugs doctor at CHNO.

Jillian Nickerson tries to repair a caught door in a newly opened room within the emergency division at Kids’s Hospital New Orleans on Aug. 20, whereas Paul Decerbo from the Rhode Island-1 Catastrophe Medical Help Workforce seems to be on.

Kathleen Flynn for TIME

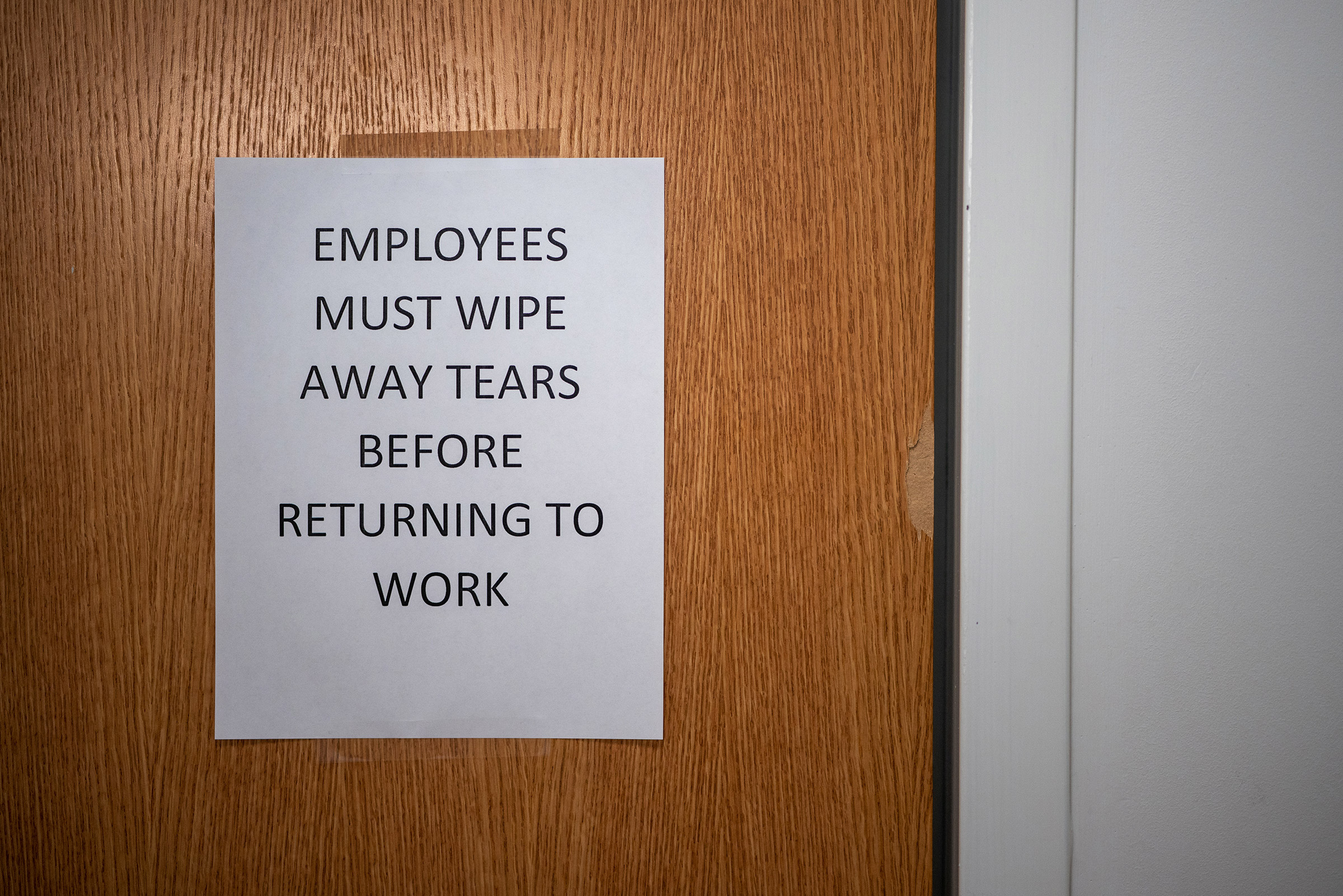

Nevertheless it’s additionally clear, he says, that the choices of unvaccinated adults are endangering the lives of youngsters who couldn’t be vaccinated even when they wished to be. Whereas many CHNO employees members are cautious to say vaccination is a private selection, there’s a discernible subtext beneath their politeness: they need extra folks locally would select to vaccinate themselves and their households. For the medical doctors who deal with younger sufferers—and who’re exhausted from worrying about COVID-19 for, as Blancaneaux says, what looks like eternally—studying that their households are unvaccinated, or failing to take different precautions, is a bitter capsule to swallow, and one which makes it troublesome to maintain going about their important work unfazed. Certainly, an indication hanging in CHNO’s emergency-department lavatory directs employees to “wipe away tears” earlier than returning to work.

“How do you attempt to inform somebody why they need to care concerning the life of a kid?” Alabama’s Kimberlin asks. “I don’t know.”

Paul Decerbo has been a member of the Rhode Island-1 Catastrophe Medical Help Workforce for greater than 10 years, lengthy sufficient to turn out to be the squad’s commander. Three months out of every yr, when there’s an emergency wherever within the U.S., Decerbo is aware of he could have to organize himself and a workforce of on-call medics, nurses and medical doctors to ship out to the scene of the disaster for 2 weeks. Typically, that’s the positioning of a pure catastrophe. For the final 18 months, it’s principally been wherever COVID-19 circumstances are surging and native hospitals are at their breaking factors.

Decerbo deployed six occasions final yr. However when he bought a name from CHNO this summer season, asking for individuals who might assist deal with emergency-department sufferers, he confronted a brand new problem. He’d want a complete workforce of individuals able to deal with COVID-19 sufferers and skilled in pediatrics—one thing not required throughout prior coronavirus surges, when the overwhelming majority of sufferers have been adults. Finally, he needed to look past Rhode Island and assemble a squad of health-care employees from a number of states to fulfill that want.

Nelson Alexis III, 17, undergoes respiratory remedy in his room at Kids’s Hospital New Orleans. Nelson, who has Down syndrome, was recognized with the virus in late July.

Kathleen Flynn for TIME

CHNO’s resident staffers weren’t fairly ready for the uptick in pediatric circumstances, both. “It was a shock,” Blancaneaux says. After a yr of few-and-far-between circumstances within the pediatric hospital, “Rapidly, eight out of the 20 sufferers I noticed [in a day] have been COVID optimistic.” It’s gotten to the purpose, he says, the place medical doctors assume any affected person who is available in with flu-like signs has COVID-19.

The hospital’s quiet environment hides the work occurring behind the scenes to maintain tempo with that enhance. CHNO has applied an incentive program to encourage present employees nurses to select up additional shifts, and has employed about 150 new nurses to assist handle the affected person load.

Maybe extra regarding, the present spike started in July, earlier than most faculties in Louisiana had began again up. As the varsity yr continues, Delta will nearly undoubtedly discover new footholds. Nobody needs to think about what occurs if that is the ascent of a bell curve, relatively than the height—significantly since vaccines for the youngest People will not be accessible till late 2021 or early 2022.

Even as soon as the pictures are licensed, youngsters too younger to consent to remedy might be reliant on their dad and mom’ willingness to get them vaccinated. That’s a troubling prospect since, in a current Kaiser Household Basis survey, solely 26% of fogeys with youngsters ages 5 to 11, and 20% of these with youngsters youthful than 5, stated they’d vaccinate their youngsters straight away.

An indication inside an emergency-department restroom at Kids’s Hospital New Orleans. “Everyone seems to be pissed off and worn out and upset,” emergency-medicine doctor Dr. Michael Blancaneaux says.

Kathleen Flynn for TIME

In some circumstances, which may be as a result of dad and mom nonetheless don’t imagine younger youngsters should be vaccinated, contemplating their low odds of dying or changing into hospitalized. However there are at all times exceptions to guidelines, they usually’re displaying up on daily basis in pediatric ICUs. Jordan Ohlsen, a nurse who works on CHNO’s acute-care flooring, says some dad and mom don’t understand how severe the virus may be till their youngster is the one in a hospital mattress. “As soon as the kid does get sick, their [parents’] conception of what the virus is [changes],” Ohlsen says. “After they are available and see their child sick, of their mind it switches to, ‘That is one thing I needs to be nervous about,’ or ‘I ought to have gotten them vaccinated.’”

If there’s any optimism buried throughout the present pediatric surge, it’s that maybe some dad and mom may have that realization earlier than their youngster will get sick, relatively than after. However with vaccine authorization for younger youngsters not less than just a few months away, the rapid battle is in convincing adults to get their pictures, thereby hopefully driving down the entire quantity of virus circulating in every group. Delta appears to be scaring not less than some holdouts into motion. On common, greater than 700,000 folks within the U.S. are actually getting a COVID-19 vaccine every day, the next quantity than the nation has reported since June. However there’s a protracted strategy to go, and never numerous time to journey it.

Significantly in areas the place an infection charges are excessive, well being officers should encourage folks to return to fundamentals, the AAP’s O’Leary says. New Orleans, for its half, has reimplemented masks mandates and now requires proof of vaccination or a damaging check from anybody who needs to go to an indoor bar, restaurant or music venue, lending a considerably subdued air to many components of the often buoyant metropolis.

“Use the mitigation measures we all know work,” O’Leary says. “Put on masks once you’re round different folks, significantly in enclosed areas….Keep away from locations the place numerous individuals are congregating.”

Catherine Perrilloux holds the hand of her two-month-old child, Carvase Perrilloux.

Kathleen Flynn for TIME

Except and till well being officers can persuade a drained and disillusioned populace to return to precautions they wished to depart prior to now, COVID-19 will maintain spreading. A small variety of sufferers, regardless of how younger, will land within the hospital. And day after day, well being care employees will don their gas-mask-like respirators, robes and goggles to look after them, many worrying all of the whereas about bringing COVID-19 house to their very own youngsters.

The employees at CHNO makes a valiant effort to remain optimistic and maintain smiling beneath their masks—a trait, maybe, of selecting to work in pediatrics. However Blancaneaux admits it may be troublesome this far right into a pandemic, when the instruments for ending it are in almost each drugstore within the nation. “Everyone seems to be pissed off and worn out and upset,” he says. “You are feeling unsupported by the general public as a result of we maintain preventing in opposition to it. And a big a part of it’s preventable.”

—With reporting by Emily Barone

[ad_2]

Discussion about this post